Mitochondria, often considered ancient relics from bacteria, are proving to be even more enigmatic than previously thought. A new study published in PLOS Biology reveals surprising findings about these organelles.

The research, titled "Somatic nuclear mitochondrial DNA insertions are prevalent in the human brain and accumulate over time in fibroblasts," uncovers that mitochondria in brain cells often transfer their DNA into the cell's nucleus. Once integrated into chromosomes, this mitochondrial DNA can have negative effects. The study involving nearly 1,200 participants found that individuals with more of these mitochondrial DNA insertions in their brain cells had a higher likelihood of early death compared to those with fewer insertions.

Dr. Martin Picard, a mitochondrial psychobiologist from Columbia University, and Dr. Ryan Mills from the University of Michigan led the study. They found that mitochondrial DNA transferring to the human genome is not as rare as previously thought. "It’s remarkable that this transfer seems to occur multiple times throughout a person's life," says Picard. The study revealed that these insertions are prevalent in various brain regions but were not observed in blood cells, which explains why past studies that focused on blood DNA missed this phenomenon.

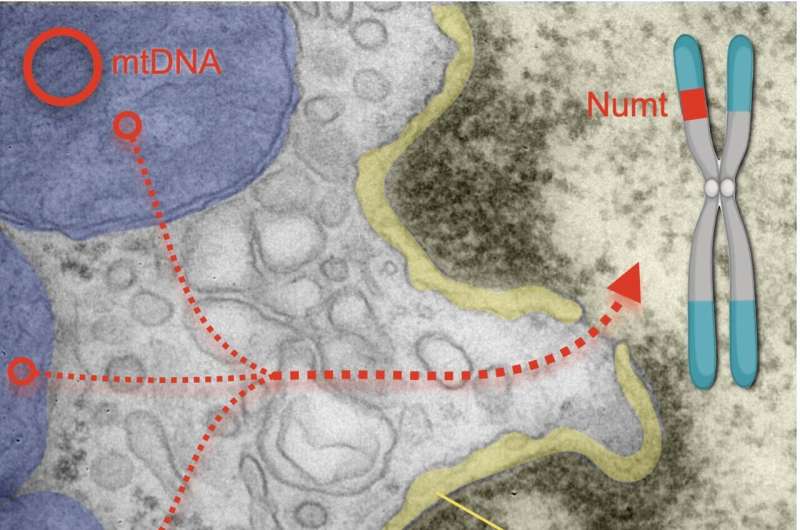

Mitochondrial DNA acts similarly to a virus, integrating into the human genome through a process akin to retrotransposons, or "jumping genes." These insertions, known as nuclear-mitochondrial segments (NUMTs), have been accumulating in our chromosomes for millions of years. While most NUMTs are benign, the current study shows that new NUMTs are still forming. They occur approximately once every 4,000 births and are one of the ways mitochondria interact with nuclear genes.

Recent research indicates that NUMTs are common in the human brain, especially in the prefrontal cortex. The study demonstrated that individuals with a higher number of NUMTs in this brain region had a tendency to die earlier. This suggests that NUMTs could influence aging, functional decline, and lifespan.

The study also explored how stress impacts NUMT formation. By examining cultured human skin cells, researchers found that stress significantly accelerates NUMT accumulation. Cells under stress accumulated NUMTs four to five times faster, highlighting a new way in which stress can affect cellular biology. Stress seems to increase the likelihood of mitochondria releasing DNA fragments that then integrate into the nuclear genome.

Dr. Picard notes, "Mitochondria are more than just energy producers; they are key players in regulating gene expression and can even alter nuclear DNA sequences." This research provides a deeper understanding of mitochondria’s role beyond their traditional function and opens new avenues for exploring their impact on health and aging.

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/alec-baldwin-torino-film-festival-121824-3cf7cfbe5c4f4bcbb9197de4de062ea6.jpg?strip=all&resize=370,370)

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/Jimmy-Fallon-and-Prince-Harry-092624-baa1362d743d4f39a7d60bf57eb6e8b2.jpg?strip=all&resize=370,370)

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/randy-moss-121324-40b858c71b0f40bfa399e2fe00152b2a.jpg?strip=all&resize=370,370)

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/scandal-kerry-washington-121824-c51a2b5f0ef741268474bec2498c285a.jpg?strip=all&resize=370,370)