Researchers from Sanford Burnham Prebys and the La Jolla Institute for Immunology have made a breakthrough in understanding senescence, a state where cells become dormant, particularly in older individuals. While this condition can have some health benefits, it may also lead to negative effects.

Senescence is not entirely detrimental. Peter D. Adams, Ph.D., director of the Cancer Genome and Epigenetics Program at Sanford Burnham Prebys, explains that it functions as a tumor suppression mechanism by halting the growth of potentially cancerous cells. Additionally, senescence contributes to wound healing by managing the repair process through inflammatory responses.

As people age and the immune system's ability to clear senescent cells diminishes, these cells can accumulate and disrupt tissue regeneration. These cells, marked by their inflammatory properties, secrete molecules that lead to chronic inflammation, a phenomenon known as inflammaging. This has been associated with several age-related conditions such as rheumatoid arthritis, liver disease, atherosclerosis, sarcopenia, and cancer.

The study published in Molecular Cell by Adams and Nirmalya Dasgupta, Ph.D., unveils a novel connection between inflammation in senescent cells and a protein involved in organizing DNA in the cell nucleus. This discovery opens up potential avenues for developing drugs that could support healthy aging by addressing the chronic inflammation caused by an excess of senescent cells.

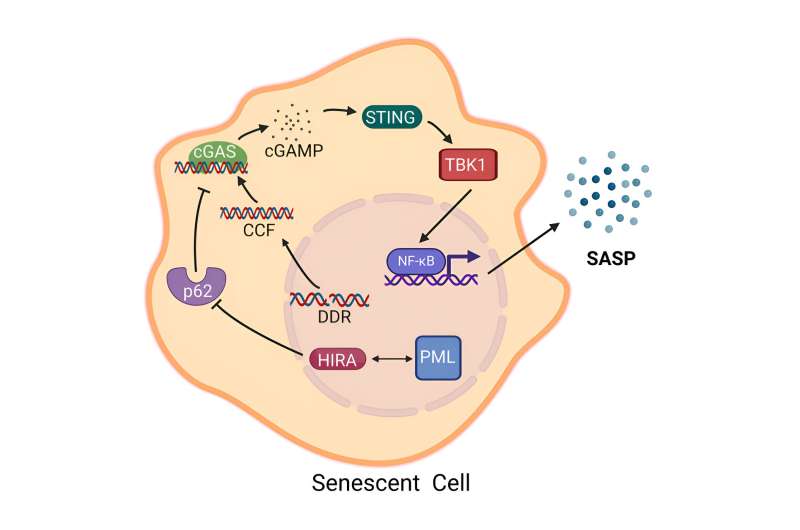

The team experimented with cells by disabling genes responsible for the HIRA protein, which is essential for DNA organization, and the PML protein, which plays a key role in anchoring proteins involved in DNA functions. They found that while these proteins did not restore cell growth, they were crucial for the release of inflammatory molecules known as the senescence-associated secretory phenotype (SASP).

Adams and Dasgupta outlined two approaches: one suggests eliminating senescent cells to improve aging, while another argues that reducing SASP-related inflammation might be a safer alternative. Their experiments showed that for senescent cells to enter an inflammatory state, HIRA must move to PML nuclear bodies. Additionally, HIRA interacts with the p62 protein, which helps mitigate the release of inflammatory molecules.

The research team plans to advance their work by collaborating with the Conrad Prebys Center for Chemical Genomics to identify small molecules targeting this newly identified pathway. They also consider repurposing existing drugs that could prevent HIRA from relocating to PML nuclear bodies, which is essential for the inflammatory process.

This study will also aid the SenNet Consortium in mapping senescent cells at a molecular level. Adams, co-director of the San Diego Tissue Mapping Center within the consortium, highlights that uncovering the gene expression and signaling pathways in these cells will facilitate the development of targeted treatments for promoting healthier aging.

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/alec-baldwin-torino-film-festival-121824-3cf7cfbe5c4f4bcbb9197de4de062ea6.jpg?strip=all&resize=370,370)

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/Jimmy-Fallon-and-Prince-Harry-092624-baa1362d743d4f39a7d60bf57eb6e8b2.jpg?strip=all&resize=370,370)

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/randy-moss-121324-40b858c71b0f40bfa399e2fe00152b2a.jpg?strip=all&resize=370,370)

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/scandal-kerry-washington-121824-c51a2b5f0ef741268474bec2498c285a.jpg?strip=all&resize=370,370)